As the calendar flips to a new month, a familiar pattern emerges in the tech journalism landscape. Publications across the spectrum eagerly publish articles that hinge on a chart produced by Statcounter Global Stats. This chart, often the centerpiece of these stories, serves as the foundation for a flurry of analysis, commentary, and speculation about the latest trends in operating system usage.

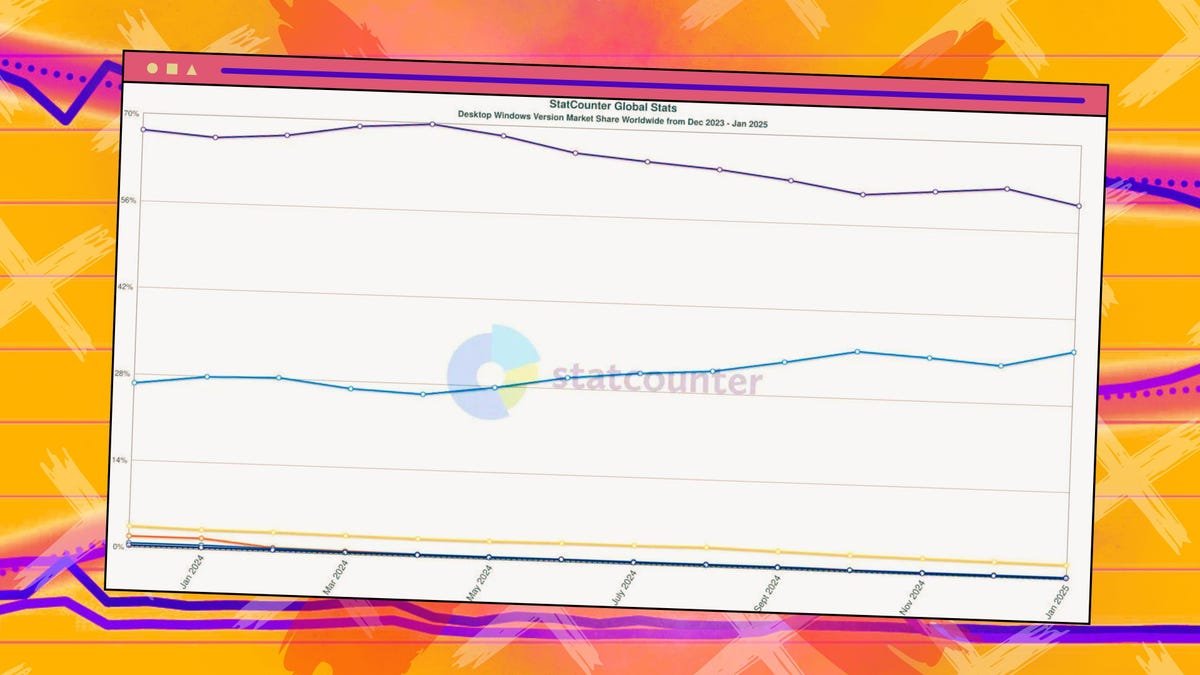

This month, the spotlight is on the apparent decline of Windows 10, represented by a prominent purple line, juxtaposed against the resurgence of Windows 11, depicted in blue. A quick glance at Google News reveals a plethora of articles already attempting to dissect these shifts, with more surely on the horizon.

Among the more audacious claims comes from Forbes, which boldly states, “The January stats are now out, and according to Statcounter, the Windows 11 upgrade trend has now un-reversed itself … some 40 million hold-outs have suddenly upgraded their PCs in the last 31 days.” Such assertions raise critical questions: “Did this really happen?” and “What does this data truly signify?”

The reality is that while Statcounter’s “market share” reports provide a convenient narrative for tech bloggers, they often lack a robust connection to the actual dynamics at play in the market. Month-to-month fluctuations frequently amount to statistical noise rather than meaningful trends.

Understanding the Data

To illustrate this point, I created a line chart using data from Statcounter, spanning from January 2022 to January 2025, focusing solely on the United States. By incorporating third-order polynomial trendlines, I aimed to capture the broader trajectory of Windows 10 and Windows 11 over time, while also indicating a margin of error.

The resulting chart tells a different story. It reveals a steady decline in pageviews from Windows 10 PCs, contrasted with a gradual increase in traffic from Windows 11 systems. These trends, while subject to some fluctuations, have remained consistent over the observed period.

It’s important to note that Statcounter’s data is derived from pageviews, not visits or sessions, which can distort the perceived popularity of each operating system. For instance, if a user navigates multiple pages on a site using Windows 11, while another user does the same on a Windows 10 device, Statcounter’s metrics may inaccurately suggest a greater prevalence of Windows 10 based solely on pageviews.

Who is Statcounter?

Founded in 1999, Statcounter is a web analytics firm based in Ireland. Initially thriving during the early days of the internet, the company provided a straightforward service for counting website hits through a tracking pixel. However, its customer base has dwindled significantly over the years, from 3 million users in 2009 to approximately 1.5 million by 2022.

As of January 2024, Statcounter’s services were utilized by only 0.5% of all websites, a figure that has continued to decline. This trend is not surprising, given the dominance of Google Analytics and other major players in the analytics space.

Where do Statcounter’s Numbers Come From?

The data reported by Statcounter aggregates pageviews from a diverse array of small to medium-sized websites. However, the company’s ability to capture a representative sample of web traffic has diminished considerably. A decade ago, Statcounter measured over 17 billion pageviews monthly; by 2022, this number had dropped to just 5 billion.

Statcounter’s data primarily reflects traffic from lesser-known sites, excluding major platforms like Google or Facebook, which skews the overall picture of web traffic. Additionally, Statcounter measures only pageviews, not visits or sessions, leading to potential misinterpretations of its “market share” reports.

So, what’s the real story?

While Statcounter’s data provides insights into the behavior of users on its client websites, it does not accurately represent the broader market share of Windows PCs. The data indicates a slow decline in traffic from Windows 10 and a gradual increase from Windows 11, but whether these trends correlate with the global population of PCs remains uncertain.

As we look ahead, the number of Windows 10 devices ineligible for upgrade to Windows 11 is likely to remain substantial, particularly as support for Windows 10 is set to end in October 2025. Accurate estimates of device populations would require access to proprietary data from Microsoft, which remains undisclosed.

For now, those relying on Statcounter’s figures should proceed with caution, recognizing the limitations of the data and the potential for misinterpretation in the fast-paced world of tech reporting.