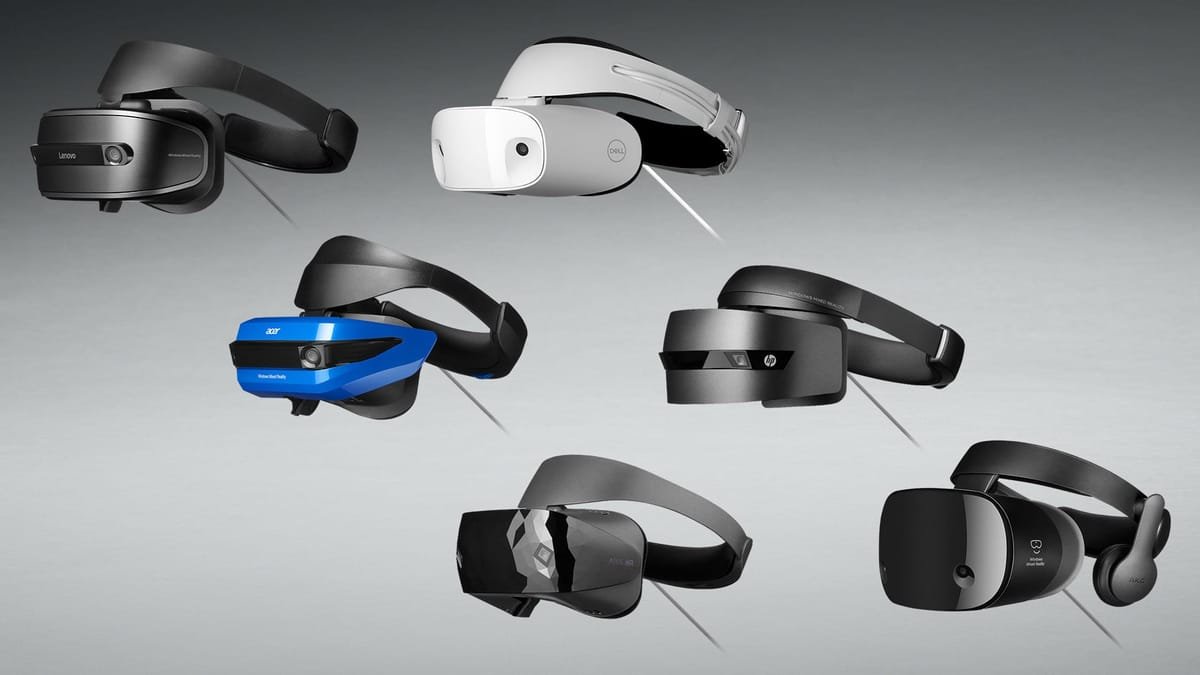

Microsoft has officially phased out Windows Mixed Reality (MR) from its latest operating system, Windows 11 24H2. This decision marks a significant shift in the company’s approach to virtual reality, as users can no longer utilize any Windows MR headsets, including popular models from Acer, Asus, Dell, HP, Lenovo, and Samsung, such as the HP Reverb G2, which debuted in 2020. The implications of this change are profound, particularly for the estimated 80,000 SteamVR users who relied on these devices, as their headsets will effectively become obsolete upon upgrading to the new version.

In a statement to UploadVR, Microsoft confirmed that this removal was intentional, a move first hinted at back in December. For those who wish to continue using their Windows MR headsets, Microsoft has advised that they remain on the current version of Windows 11 (23H2) until at least November 2026, thereby avoiding the upgrade to 24H2.

“Existing Windows Mixed Reality devices will continue to work with Steam through November 2026, if users remain on their current released version of Windows 11 (version 23H2) and do not upgrade to this year’s annual feature update for Windows 11 (version 24H2).”

This announcement coincides with the end of production for HoloLens 2, another indication of Microsoft’s shifting priorities in the realm of augmented reality (AR). Software support for HoloLens 2 is set to conclude after 2027, further signaling a retreat from hardware development in this space.

Windows MR Never Really Took Off

Despite its promising name, Windows MR was primarily a virtual reality platform, compatible with a wide array of SteamVR content through Microsoft’s dedicated driver. The initial wave of Windows MR headsets launched in late 2017, aiming to compete with established players like the Oculus Rift and HTC Vive. They introduced innovative inside-out positional tracking, a feature that was groundbreaking at the time.

However, the headsets faced significant challenges. Most manufacturers, excluding Samsung, adopted a cost-effective single-panel LCD design, which lacked the advanced features found in competitors’ offerings. The Samsung Odyssey stood out with its adjustable interpupillary distance and OLED panels, yet it was not enough to sway the market. Despite aggressive pricing, with some models available for as low as 0, Windows MR struggled to capture the attention of PC VR gamers. By 2019, Windows MR usage peaked at around 10% on Steam, but has since dwindled to approximately 3.5%.

The limitations of the tracking technology played a crucial role in this decline. Unlike the Oculus Quest and other headsets that utilized multiple cameras for expansive tracking capabilities, Windows MR headsets were equipped with only two forward-facing cameras, restricting the range of motion for users. Although the HP Reverb G2 attempted to rectify this with additional side cameras, it arrived too late to revitalize the platform.

Moreover, the ergonomics of the controllers left much to be desired, often feeling more like budget options than premium gaming accessories. This was in stark contrast to the highly regarded Oculus Touch and Valve Index controllers, which garnered loyal followings among users.

Ultimately, Microsoft and its partners failed to present a compelling case for consumers to invest in the initial lineup of Windows MR headsets. By the time HP introduced the Reverb with its high-resolution display, Meta’s Oculus Quest series had already begun to dominate the market, offering a versatile and affordable alternative that appealed to a broader audience.

In recent years, Microsoft has redirected its focus toward a software-centric partnership with Meta, leading to the integration of Xbox Cloud Gaming and Office web applications into the Horizon OS of Quest headsets. This strategic shift underscores a broader trend in the tech industry, where collaboration may prove more fruitful than competition in the evolving landscape of mixed reality.